Eggs

Eggs have become such a part of our breakfast menu that, except to decide whether to have them fried or scrambled, most of us don't give them a second thought. We eat them with our buttered toast and never even wonder how they developed. If someone asked you to describe an egg, you wouldn't have any problems because everyone knows that an egg is a small, shell-covered object that contains a yellow yolk and a substance called egg white. Although this general description is true, if you look more closely, you will discover that an egg is much more complex.

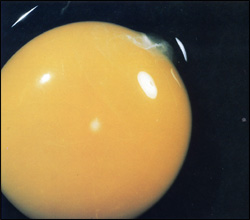

Located in almost the exact center of this unfertilized egg yolk is the white germ cell area. In a fertilized egg, this area is the oint at which the young chick begins to develop. (The two brighter spots on the yolk are reflections of the lights used to photograph the egg.)

Perhaps the easiest way to study an egg is to go back to the beginning when it is just a cell inside the female bird and follow along on its step-by-step development. When a female bird is hatched, she already has inside her body the germ cells of more eggs than she will probably lay in her entire lifetime. At the age of three months, the young bird forms the first coating of yolk around one of these cells. As this yolk begins to develop, another cell receives its first coating. This action, repeated in assembly-line fashion, ensures that there will be several yolks in various stages of development inside the female bird at all times.

Microscopic studies have shown that an egg yolk is made up of six rings, each with a white and a yellow layer. These layers are added to the cell in a strict rhythm determined by the position of the sun – the yellow layer during the day and up until midnight, and the white layer between midnight and sunup.

The springtime presence of a male bird causes a hormone change in the mature female, bringing about the creation of the final yolk layer. His courtship then triggers the finished yolk to break loose and fall into the oviduct, a tube that serves as a passageway for the egg as it moves through the next stages of development. Most wild birds cannot lay eggs if there is no mate, but this is not true of domestic chickens, ducks, and pigeons. Records show that one leghorn hen laid 1,515 eggs over an eight-year period and never saw a rooster.

If successful mating takes place, the egg is fertilized as it travels down the funnel-like oviduct. Unsuccessful mating or the absence of a male, as in the chicken's case, produces an infertile egg, which will not develop into a young bird. It takes about twenty minutes for the yolk to travel down to that part of the oviduct where the albumen (al-BYOu-men) or egg white is produced. This albumen, like the yolk, is made up of several layers and is gathered by the yolk over a three-hour period. The first layer is but a thin covering; the second is dense and tough. It serves as a shock absorber to protect the cell during the egg's drop to the nest and during the shifting and turning of the eggs by the female throughout incubation. As the egg spirals down through the oviduct, a light, watery third layer of albumen is forced through the denser second layer and up against the yolk. The yolk now floats in this watery fluid, and the tiny cell comes to the yolk's surface.

One-fourth of all bird species lay white eggs; the shells of the rest, such as these bluebird eggs, are colored.

If you have ever looked closely at an egg before it has been cooked, you may have seen the original germ cell. It looks like a small white speck on the yolk. You may also have noticed the milky ropelike matter attached to the yolk ends. These "ropes" are formed as the spiraling motion of the egg twists the albumen at either end of the yolk, and they keep the yolk anchored in the center of the egg. During incubation these ropes break, and the female bird must turn the eggs occasionally to keep the yolks centered.

When the egg has received all of its albumen layers, it moves on to be wrapped in two white sheets of tough membrane. Formation of these membranes takes about an hour and ten minutes. Then the egg drops into the shell-producing area of the oviduct.

Here it stays for about nineteen hours while the shell is added in four porous layers. During the last of these hours, the shell receives its coloration. Al-though one-fourth of all bird species lay white eggs, the rest are colored in some manner. They may be spotted, blotched, or marbled with various colors, or they may be a solid color such as olive green or sky blue. The last eggs laid in the nest are often paler or have fewer spots than the first ones. Coloration also can vary from one bird to another within the same species. Since color pigments are obtained from the food eaten by the female, a difference in diet may be the reason for these shell color changes. Yolk color also depends upon the food eaten by the female. You may have noticed that your breakfast eggs sometimes vary from a pale yellow to a dark orangish yellow. Egg yolks of wild birds vary from very pale yellow to a dark red that is almost a maroon.

Once the egg is laid, air enters through the pores in the shell, and an air pocket is formed at the blunt end of the egg between the two membranes. This air cell provides oxygen for the developing bird during incubation.

Occasionally an abnormal egg is produced when something goes wrong with this natural assembly line. Double- or triple-yolked eggs occur when two or three yolks enter the oviduct at the same time and all are surrounded by the albumen, membranes, and shell of a single egg. Such eggs are considered rare. Records show that only one out of every five hundred thousand chicken eggs has two yolks and one out of every 25 million has three yolks. Yolkless eggs also may occur if something prevents the yolk from entering the oviduct. In this rare case only the white gets enclosed in the shell and the egg is usually smaller. A chicken's yolkless egg will be about the size of a pigeon's normal egg.

If something goes wrong with the shell-secreting area or if the bird's diet has an extreme lack of calcium, a "soft-shelled" egg may be laid. This egg will be surrounded by only the two membranes. These abnormalities, although described for the domestic chicken, also occur among the eggs of other birds. However, considering the number of eggs produced, the errors are quite small.

Tomorrow morning as you eat your breakfast, stop and think about that egg on your plate and the miraculous assembly line from which it came.

Ilo

Hiller

1989 – Eggs: Introducing Birds to Young

Naturalists. The Louise

Lindsey Merrick Texas Environment

Series, No. 9, pp. 9-11.

Texas A&M University

Press, College Station.